Incunabula

Gutenberg’s invention of the mechanical printing press became operational in Germany around 1450, and spread quickly to other European countries. The invention ushered the first mass democratization of knowledge in history, taking books outside the confines of the privileged and making them accessible to the public at large. In particular, the printing technology became the main driver of the Renaissance movement that rediscovered classical philosophy, literature and art between the 14th and 17th century, and facilitated the transition of western culture, economy and politics from the Middle Ages to modern times.

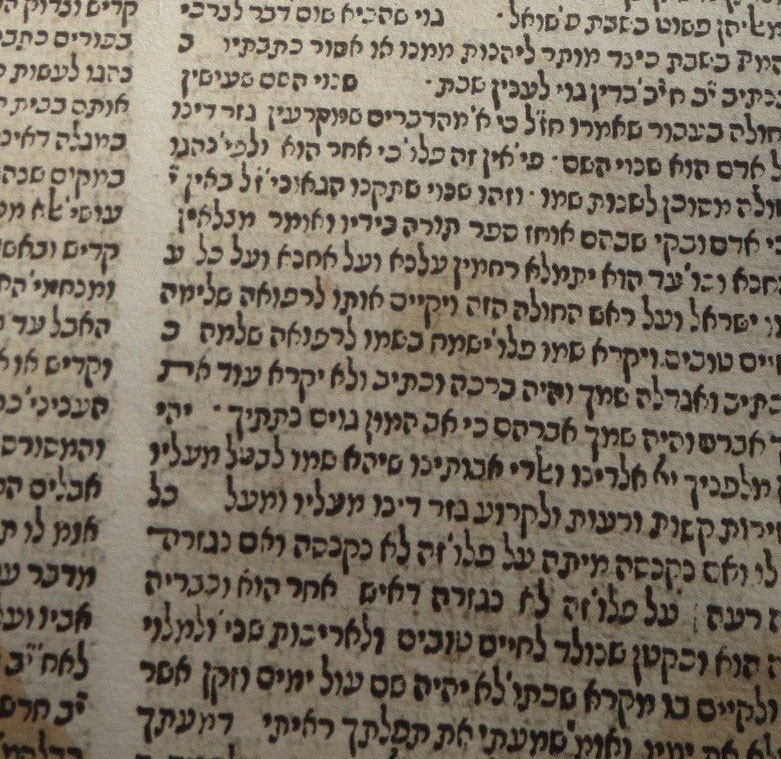

The first generation of books printed between the years 1450 and 1501 is known as incunabula, meaning the “cradle”, or very early stages of, the printed book. About 30,000 incunabula were printed before 1501, of which only 150 Hebrew books survived in the 20th century, mostly in single and often incomplete copies. These incunabula are considered the most treasured possessions of libraries and private Hebrew collections around the world, and indicators of the collection’s Importance.

Schocken began collecting Hebrew incunabula as early as 1913, and kept expanding his collection throughout his life. He amassed 100 Hebrew incunabula, forming the largest collection in private hands. In 1930 Schocken gave 64 incunabula to the National Liibrary, which later became part of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Among them were the first printed Passover Haggadah (printed in Guadalajara, Spain, circa 1482), tractates of the Babylonian Talmud (printed in Soncino, Italy, in late 1480s), and especially important prints from the Iberian Peninsula, printed before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. One of Schocken’s prize Incunabula was “Behinat Olam”, published by Estellina Conat, the first woman involved with Hebrew printing. It was published in Mantua, Italy, circa 1474.

Schocken was extremely fond of his incunabula collection. When traveling around the world, he always took with him rare books from the collection. When in 1942 the exiled German-Jewish writer Karl Wolfskehl met Schocken in Australia, he was intrigued that the only reading material Schocken carried on his person “was a magnificent 15th century miniature prayer book, printed by the Soncinos”, the famed Jewish family of printers during the Italian renaissance. The book was carefully wrapped in a soft leather case. “I was just as moved as Schocken”, Wolfskehl wrote, “by the mystery of the book’s inviolable and unassailable holiness.”